Download this Brief as a PDF: ![]()

English | Français | Português

Summary

Nigeria’s long-running “indigene-settler” conflict in and around Jos, Plateau State has escalated in recent years and may spread to other ethnically mixed regions of the country, heightening instability. Navigating such inter-communal fault lines is a common challenge for many African societies that requires looking past symptoms to address systemic drivers. In Nigeria, this will entail measures that directly mitigate violence as well as realize constitutional reform.

(Photo: sohyb09)

Highlights

- Nigeria’s statutory framework grants local officials the authority to extend or deny basic rights to citizens in their jurisdictions, thereby creating incentives for the politicization of ethnicity and escalating intercommunal violence.

- Ineffective state responses to repeated ethnic clashes have highlighted a lack of political will to address this violence.

- While currently concentrated in central Nigeria, the systemic drivers to identity conflict have the potential to spread elsewhere in the country and will require fundamental institutional reforms to resolve.

In extreme cases, rival communities may perceive that their security, perhaps their very survival, can be ensured only through control of state power. Conflict in such cases becomes virtually inevitable.

—“The Causes of Conflict and the Promotion of Durable Peace and Sustainable Development in Africa,”

Communal clashes across ethnic and religious fault lines in and around the city of Jos in central Nigeria have claimed thousands of lives, displaced hundreds of thousands of others, and fostered a climate of instability throughout the surrounding region.

While large-scale violence has occurred periodically over the past decade, in recent years attacks have become more frequent, widespread, and efficient. Over 200 people were killed and nearly 100 more went missing during near daily attacks in January 2011. Many Report of the United Nations Secretary-General, 1998 victims were killed or seized by Muslim or Christian youth gangs at impromptu roadside checkpoints and taxi and bus stations, their bodies later found in nearby shallow graves.1

Several major attacks in 2010 saw new, increasingly lethal tactics. During 4 days of fighting in January, up to 500 people were killed and some 18,000 displaced, many into neighboring states. Local organizations collected over 150 text messages circulated prior to the violence, revealing an orchestrated effort to stoke tensions. In March, a single attack left another 300 to 500 dead. In August, five men were arrested while attempting to smuggle rocket launchers, grenades, AK–47s, and large quantities of cash into Plateau State, of which Jos is the capital. On Christmas day, twin car bombs in Jos killed nearly 80 and wounded more than 100. Signaling a dangerous new turn to this conflict, the violent Islamist group Boko Haram claimed responsibility for the explosions. The group had previously only been active in northern Nigeria.

The conflict in Jos is often characterized as inter-religious or inter-ethnic, mainly between the Christian-dominated ethnic groups of the Anaguta, Afizere, and Berom, and the predominantly Muslim Hausa and Fulani groups. But, as is often the case with identity conflicts in Africa, these are socially constructed stereotypes that are manipulated to trigger and drive violence in Jos.2 They veil deeper institutional factors within Nigerian law that are abused and exploited to deny citizens access to resources, basic rights, and participation in political processes— factors that, left unaddressed, have the potential to trigger violence across the country.

Government responses to the conflict are widely perceived as ineffective. At least 16 public commissions have been launched to examine the conflict and identify solutions, and many other studies have been conducted by independent groups. But there is little political will to act on these findings. Recommendations go largely unheeded. Nor have organizers and perpetrators of attacks been prosecuted. Federal and state governments have regularly worked at cross-purposes. While civil society groups have become increasingly engaged, this has had a polarizing effect in some cases.

Underlying Causes

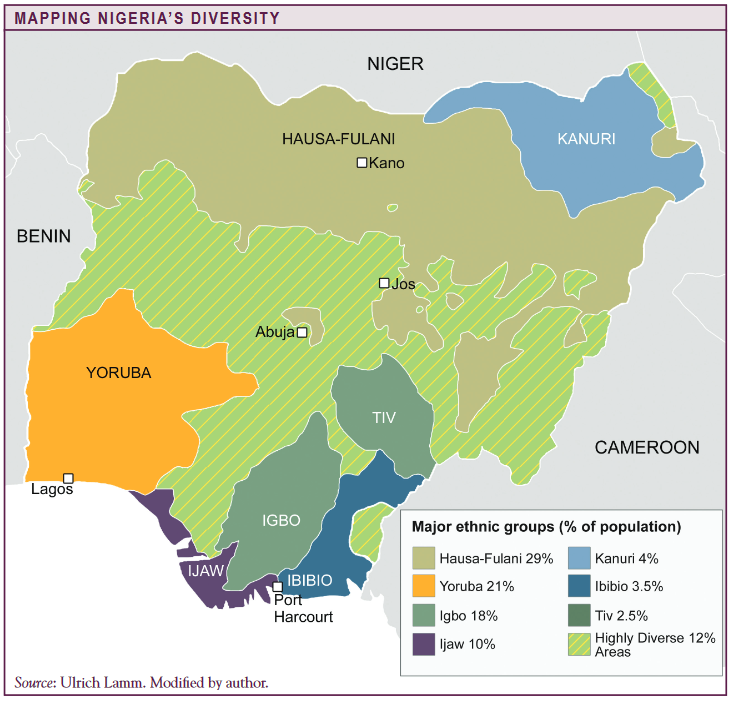

Situated on the northern edge of the so-called middle belt in central Nigeria where the country’s predominantly Muslim northern half blends with the generally Christian south (see map), Jos is a relatively new city. It was established as a mining transportation camp in 1915 because of its proximity to nearby tin and columbite deposits. With a mild climate, high quality soil, abundant water resources, extensive grazing lands, and economic opportunities, it attracted migrants from around Nigeria and currently has a population of nearly 1 million. The city remains a key supplier and commercial center in the national livestock trade and is the site of the National Veterinary Research Institute. Before being destroyed during communal clashes in 2002, the Jos Central Market was one of West Africa’s biggest on account of its proximity to a high-traffic rail juncture between northern and southern Nigeria. The city’s diverse population once exemplified the Plateau State slogan, “the home of peace and tourism.” Schools were often intermixed, and business was conducted regardless of religious or ethnic affiliation.3

This began to change in the early 1990s following an adjustment in the distribution of indigeneship certificates. In Nigeria, indigenes are “original” inhabitants of a local government area, or members of those ethnic groups that trace their lineage back to the area. All others are considered “settlers,” or migrants. The distinction was initially intended to allay concerns among minority groups who feared that their traditional customs and authority structures would be overwhelmed and eroded by the expansion of larger ethnic and religious groups. However, in practice, the classification has often been used to determine who “belongs” to a particular locality, which in turn determines whether citizens can participate in politics, own land, obtain a job, or attend school.4 Accordingly, the indigeneship certificate is now a defining document in the day-today lives of many Nigerians.

Such differentiations are grounded in national law. The Nigerian constitution, adopted in 1999, and the Federal Character Commission, a statutory body established to ensure equity in the distribution of resources and political power in the country, recognize the validity of indigene certificates. These bodies also accept the authority of local officials to issue the certificates to constituents whom officials deem qualified—a practice that first originated in the 1960s. This authority dramatically elevates the importance of and competition over districting and local elections. Elected officials, in turn, have a strong incentive to use the certificates as a tool to consolidate local ethnic majorities. Indeed, many are accused of stirring tensions, supporting violent actors, and perpetuating the selective distribution of indigene certificates, including the Governor of Plateau State, Jonah Jang, whose political campaigns have seemed to vilify Muslims and certain Christian ethnic groups.5 This has resulted in sharp differences in intergroup inequality, intercommunal animosity, and social fragmentation.

Defining indigeneship is extraordinarily arbitrary. For instance, a Hausa, Igbo, or Yoruba—groups that tend not to be originally from Jos—could legally be deemed a settler and denied a certificate even though his family has lived in Jos for generations. Were this same individual to return to areas where his ethnic group predominates, local officials could similarly deny certificates on account of his birth and connections in Jos. Children of inter-ethnic and inter-religious parents face similar double-standards.

“The ethnic or religious dimensions of the conflict have subsequently been misconstrued as the primary driver of violence when, in fact, disenfranchisement, inequality, and other practical fears are the root causes.”

But for many years, this was not a problem. Certificates were generally easy to obtain for Plateau State residents and caused few concerns. However, during the late 1980s falling government revenues, increasing economic pressures, and steadily increasing migration to one of Nigeria’s fastest growing regions prompted some local authorities to revise indigene certificate policies. In 1990, several local jurisdictions in Plateau, including Jos, began to restrict the distribution of indigene certificates.6 Under Nigerian law, the modifications were perfectly legal, but the action seemed to deny indigeneship eligibility disproportionately to many Muslims and ethnic groups from northern Nigeria. These groups in turn lobbied for assistance from national authorities. In 1991, General Ibrahim Babangida, the (northern-born) military ruler of Nigeria, announced that Jos would be divided into three Local Government Areas (LGAs) in what many perceived as a thinly disguised effort to gerrymander the region in favor of his local allies who would then control certificate distribution. Some groups, particularly Christians, feared this decision was designed to exclude them from political office.

As uncertainty mounted over access to indigeneship certificates, community relations deteriorated. Yet violence did not immediately break out. Babangida’s successor as military ruler, General Sani Abacha, dissolved all democratic structures and in 1994 directly appointed military governors, who then selected local government officials. Abacha’s appointments prompted local protests and counterdemonstrations in Jos. Fears and tensions reached a breaking point, leading to the first violent communal clashes and deaths. Ever since, local elections and political appointments have been viewed as winner-take-all contests.

The ethnic or religious dimensions of the conflict have subsequently been misconstrued as the primary driver of violence when, in fact, disenfranchisement, inequality, and other practical fears are the real root causes. Capitalizing on such conditions, many political rivals have instrumentalized the ethnic and religious diversity of Jos to manipulate and mobilize support. Each outbreak of violence worsens suspicions and renders communal reconciliation more difficult, deepening the cycle and further incentivizing polarization. The heads of the Christian Association of Nigeria and the Nigerian National Supreme Council for Islamic Affairs issued a joint statement in 2010 denouncing local politicians in Jos for exploiting communal tensions for personal gain.7 A study commissioned by the Office of the President in 2003 similarly concluded that while ethnic plurality plays a role in the conflict, “underpinning these sources of antagonism and triggers are deeper systemic issues at the center of which is the relationship between political power and access to economic resources and opportunities.”8

“Since communal violence first emerged in 1994, few charges have been brought against perpetrators and no credible prosecutions have been pursued.”

Similar indigeneship tensions have emerged elsewhere in Nigeria. Reflecting a widespread concern over the potential expansion of these disputes, 20 Nigerian citizens filed a joint legal case in March 2011 against the federal and 16 state and local governments regarding discrimination on the basis of indigeneship.9 The plaintiffs argue they are being denied fundamental rights protected by the Nigerian constitution as well as the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights, the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights, and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. All are long-time residents of the jurisdictions against which they are filing claims, some with family roots going back generations.

Indigeneship has also sparked deadly communal conflict in Kaduna State in northern Nigeria and the oil-rich southern Delta State. As in Plateau, these conflicts have been described as inter-religious or inter-ethnic, though the material ramifications of losing indigeneship are the real drivers of violence. The conflict in Jos, however, is more violent, likely as a result of how intensely indigeneship has been seized by political rivals to mobilize support in these closely divided jurisdictions. According to 2011 voter registries, the Christian-dominated ethnic groups made up approximately 200,000 while predominantly Muslim groups number roughly 150,000 out of 429,179 registered voters in Jos North LGA—the central district of the greater Jos area.

Governance Shortcomings Exacerbate Tensions

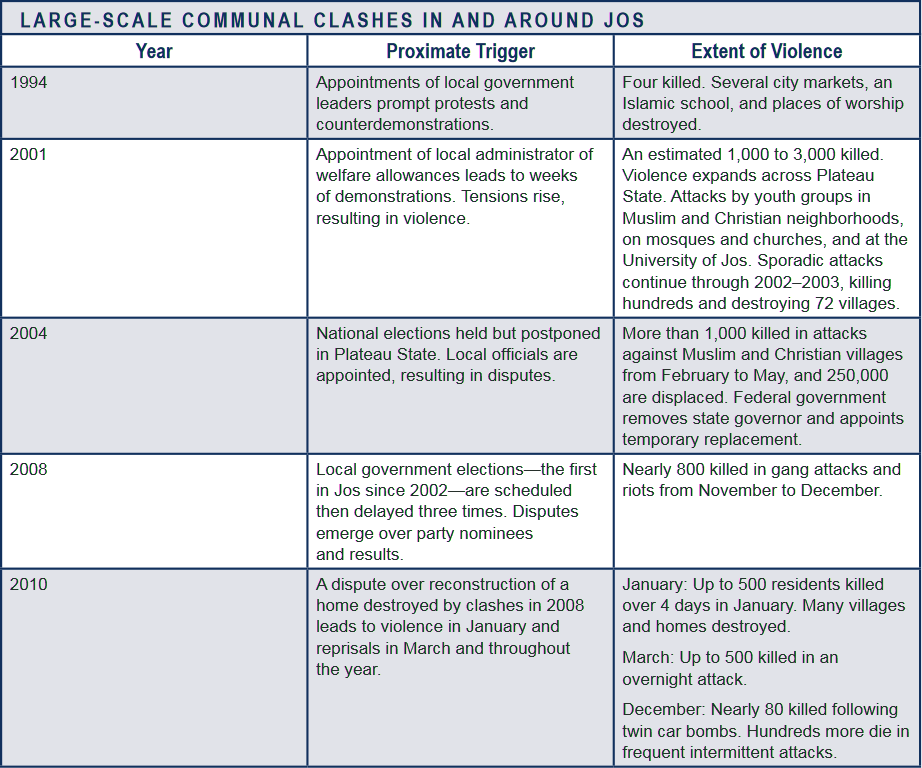

To deter attacks and protect the people in Jos, an already extensive national police presence has regularly been augmented by military deployments. Yet on multiple occasions security agencies have failed to prevent and respond to known threats and early signs of pending attacks. The worst outbreaks of communal clashes in 1994, 2001, 2004, 2008, and 2010 (see table) were typically preceded by days of simmering tensions and conspicuous mobilization. Prior to fighting that resulted in thousands of deaths in 2001, “everyone on the streets of the town sensed the tension and the threat of danger hanging heavily in the air long before the events. . . . Something dreadful was about to happen.”10 During incidents in 2010, separate attacks began and ended at roughly the same time on the same day, suggesting they were preplanned.11

Prevention and response are further undermined by poor intergovernmental coordination and insufficient means of information-sharing. For instance, in March 2010, Plateau State Governor Jonah Jang informed the commanding officer of an armored division of the Nigerian army deployed to Jos of an impending attack on the Dogo Na Hawa village through text message. The governor later claimed a text was necessary as the officer refused to respond to his phone calls. A subsequent attack left more than 300 dead.

“A governance vacuum in Jos is worsening; increasingly fearful and suspicious communities are turning toward nonstate actors.”

Part of the problem is disconnected lines of authority. Police and the armed forces are centralized at the federal level, and all related security requests must be channeled to the national capital for consideration. This poses serious challenges for early response and management of internal security at the state and local levels. Following attacks, finger pointing and blame trading within the security sector and across the government are common. This is compounded by episodes in which some of the perpetrators of the ethnic violence are seen wearing military or police uniforms.

Justice and accountability have also been lacking. Since communal violence first emerged in 1994, few charges have been brought against perpetrators, and no credible prosecutions have been pursued.

The highly connected individuals and politicians involved in fomenting tensions are equally effective in using their influence to protect perpetrators of violence. With each passing incident of violence that results in few arrests and no prosecutions, citizens’ confidence in law enforcement, judicial institutions, and government, in general, diminish.

“The concept of indigeneship inherently divides Nigerians and undermines the democratic form of government that Nigeria aspires to uphold.”

While on-the-ground response has remained poor, government offices at the state and national levels have launched numerous studies of the violence in Jos, but with little effect. After one clash in 2008, five separate commissions of inquiry were announced. Yet few if any of the resulting policy prescriptions have been implemented. Some commission reports have never even been made public. Reflecting the growing impatience and diminishing expectations of many Nigerians, one newspaper editorial described such commissions as a “ritual of instituting inquiries and receiving reports that always end up in the archives.”12 With their proliferation, these committees have lost credibility and been politicized. Recent commissions have been unable to obtain testimony from key sources and attract high-profile members. Some commissions have been overtly one-sided.

As a result, a governance vacuum in Jos is worsening. Increasingly fearful and suspicious communities are turning toward nonstate actors. Citizens rely almost entirely on these groups for protection, humanitarian assistance, and reintegration of displaced persons in the aftermath of conflicts, which further amplifies the polarization resulting from indigeneship disputes.

Some community organizations seem intent to hasten this polarization. Several faith-based organizations—Christian and Muslim alike—and many youth groups such as the Berom Youth Movement, Anaguta Youth Movement, Afizere Youth Movement, and the Jasawa Development Association have played key roles in spreading exclusionary ideologies and violence. In the absence of credible and accountable state authorities, their influence and appeal among citizens of Jos can only be expected to grow.

Mitigating Future Conflict in Plateau State

Entrenched institutional factors are at the heart of the accelerating distrust and violence in Plateau State. Left unchecked, this pattern is likely to expand to a growing number of Nigeria’s 36 states. Fundamental changes will be required to reverse the incentives feeding this violence.

Eliminate indigene/settler classifications in government decision making.

The legal basis for indigeneship in the Nigerian constitution and Federal Character Commission should be eliminated. Originally envisioned as a means to protect traditional customs, cultures, and governance structures, the notion of indigeneity has been warped and politicized. Today, it provides an institutionalized incentive for political opportunists to build power on the basis of exclusion. In Jos, it has led to thousands of deaths and severe intercommunal hostility. The concept of indigeneship inherently divides Nigerians and undermines the democratic form of government that Nigeria aspires to uphold. Indeed, it undercuts the very notion of what it means to be Nigerian.

Disentangling indigeneship from Nigerian law will be difficult. It will likely require amendments to the Nigerian constitution and other legal codes. To the extent such categories ever had value, in an increasingly mobile, modern, and urban society, they are now outdated. Likewise, increasingly popular halfmeasures should be dismissed. Clearer definitions of “indigenes” or supplemental “residency certificates” for so-called settlers will not eliminate the two-tiered notion of citizenship that the indigene/settler dichotomy perpetuates. Indigeneity should end or conflict in Jos is likely to worsen—as well as emerge in other Nigerian cities and states.

Strengthen, coordinate, and deconflict security institutions.

Strengthening security forces’ capacity to proactively detect early warning signs and respond to intercommunal tensions can help better contain outbreaks of violence. This will require a cohesive intelligence capability that can provide local and state law enforcement units with near-time information. At the same time, federal forces must remain engaged at the local level to protect minorities. However, clear lines of authority and means for coordination between the local, state, and federal levels need to be put into practice. Similarly, means for investigating allegations of security sector participation in ethnic violence are required to ensure accountability.

Progress in Lagos State could inspire innovative reforms in Plateau. Lagos established a state security trust fund that serves as a point of coordination between business and state officials to identify security threats and coordinate responses with police authorities. It also mobilizes funds and resources to support local policing. Helicopters, vehicles, and other advanced equipment have been purchased to enhance police effectiveness and incentivize quick response and information-sharing. Other policing initiatives in Lagos have successfully integrated some youth groups in community policing and monitoring efforts.

Make protection of minority rights a priority.

In order to reconcile Plateau’s polarized ethno-religious identity groups and build support for peacebuilding initiatives, all sides must have confidence that basic rights will be protected and that an institutionalized means to investigate alleged violations is available. This will require the engagement of a trusted, independent, external actor.

The National Human Rights Commission is positioned to play such a role. In March 2011, President Goodluck Jonathan signed into law amendments aimed at empowering the previously hamstrung commission. Its capacity, budget, and authority should now be expanded in order to fulfill this broader mandate. It would do well to emulate successes achieved by Ghana’s Commission for Human Rights and Administrative Justice, which has contributed significantly to social reconciliation. This commission is wholly independent from, though collaborates with, the security services. This arrangement facilitates greater cooperation from citizens who are more inclined to report violations and abuses to the trusted human rights commission. Additionally, Nigeria’s human rights commission must have the authority to initiate and conduct investigations, issue subpoenas, access state and national leaders, pursue charges, and other prerogatives in order to cut through political stonewalling.

Such an expansive mandate will require the appointment of leaders with unquestionable integrity and insulation from political pressures. To foster this, leadership appointments should be subject to peer review from respected civil society entities such as the Nigerian Bar Association. Indeed, given that some politicians and politically connected individuals will likely be the subjects of investigations, the commission will need to remain consciously disentangled from politics.

Establish community-based, state-supported peacebuilding committees.

The Plateau State government, in collaboration with federal counterparts, should establish community-based interethnic and -religious peacebuilding committees to facilitate dialogue and implement conflict mitigation strategies.

The Plateau State government should model these committees on those in Kaduna State, where the government proactively involves the population in forums for dialogue such as the Committee on Inter-Religious Harmony chaired by the governor. The committee is designed to identify potential conflict flashpoints as well as devise steps to avert or resolve them. It also works to ensure the speedy repatriation, rehabilitation, and palliative compensation of displaced persons and monitors the flow of small arms.

Such a committee in Plateau could lay the foundation for sustainable stability by emphasizing reconciliation and fostering a climate of political inclusiveness. It could also bear immediate results by providing a means for government-community engagement and facilitating more timely interventions that can prevent localized incidents from escalating to large communal clashes. Over the long-term, such an initiative can help inculcate a shared sense of Nigerian identity.

Conclusion

In many respects, the spiraling insecurity in Jos is anything but a local communal conflict. Its root causes and impacts encapsulate many of Nigeria’s biggest political challenges. Unclear and discriminatory legal codes fuel conflict, warp political dynamics, and undermine democratic progress. Governance shortcomings create vacuums in which citizens are forced to turn to self-help solutions such as ethnic associations or vigilante groups. A modern economy conducive to local entrepreneurship and appealing to foreign investors remains impossible while the free flow of people, goods, and ideas is restricted by indigeneship and resulting instability. Resolving the conflict in Jos will require looking past the symptoms of Nigeria’s ethnic and religious divisions to focus on the institutionalized inequities that encumber not only stability in Plateau State but also progress in Nigeria as a whole.

Chris Kwaja is a Lecturer and Researcher in the Centre for Conflict Management at the University of Jos, Nigeria

Notes

- ⇑ Shuaibu Mohammed, “Buildings Burn, Death Toll Mounts in Central Nigeria,” Reuters, January 30, 2011.

- ⇑ Clement Mweyang Aapengnuo, “Misinterpreting Ethnic Conflicts in Africa,” Africa Center for Strategic Studies, Africa Security Brief No. 4, April 2010.

- ⇑ Abubakar Sokoto Mohammed, “The Impact of Conflict on the Economy: The Case of Plateau State of Nigeria,” Overseas Development Institute, 2004.

- ⇑ “‘They Do Not Own This Place’: Government Discrimination Against ‘Non-Indigenes’ in Nigeria,” Human Rights Watch, April 2006.

- ⇑ Philip Ostien, “Jonah Jang and the Jasawa: Ethno-Religious Conflict in Jos, Nigeria,” Muslim Christian Relations in Africa, August 2009, 19.

- ⇑ Human Rights Watch; see also Jane Krause, “Explaining Nigeria’s Christmas Killings,” OpenDemocracy.net, January 3, 2011; “Plateau: Home of Pieces and Terrorism,” Sahara Reporters, July 15, 2010.

- ⇑ “Jos Bombing: Politicians ‘Fuel Nigeria Unrest,’” BBC, December 28, 2010.

- ⇑ Strategic Conflict Assessment: Consolidated and Zonal Reports (Abuja, Nigeria: Institute for Peace and Conflict Resolution, March 2003), 160.

- ⇑ “Nigeria: Constitutional challenge to indigene-settler divide heard March 14, 2011,” Institute for Human Rights and Development in Africa, March 14, 2011.

- ⇑ Umar Habila Dadem Danfulani and Sati U. Fwatshak, “Briefing: The September 2001 Events in Jos, Nigeria,” African Affairs 101, no. 403 (April 2002), 248.

- ⇑ Adam Kigazi, The Jos Crisis: A Recurrent Nigerian Tragedy, Discussion Paper No. 2 (Abuja, Nigeria: Friedrich Ebert Stiftung Nigeria, January 2011), 27.

- ⇑ “The Presidential Panel Report on Jos Crises,” Daily Trust, September 2, 2010.